The ZEVs are coming—and leading bulk haulers are gearing up now

Cox Petroleum president and CEO Jeremy Mairs captured in one sentence what many tank truckers were thinking while listening to Quantix’s Troy Basso and Peterbilt’s Dusty Garland discuss their experience with fleet electrification.

“I don’t like anything you have to say,” he summarized, as diplomatically as possible.

“But I’m sitting here like, ‘OK, what do I need to do?’ I’m trying to be a smart businessman. But how much do [battery-electric trucks] cost? Are my customers going to appreciate getting 20% less product every load at a higher rate [because of the battery’s weight reducing payload capacity]? And I’m going to be delivering fuel in an electric vehicle, so when I try to pull into a loading rack, are they even going to let me in?”

All good questions, to be sure, and plenty more are worth asking.

Unfortunately for Mairs, the answers aren't as abundant—and even if they were, it doesn’t matter.

The first milestone in the ACF rule’s aggressive ZEV phase-in schedule is Jan. 1, 2025.

“The expectation is by the spring of 2023, they’re going to pass this regulation, in largely the same version we’ve seen, with a few modified items, like refined definitions, and maybe clarified or additional detail in the exemptions, but without changing the overall effect of this rule, and it’s going to be hard to make everybody happy,” Sean Cocca, policy compliance director with clean transportation and energy consultancy Gladstein, Neandross & Associates (GNA), told Bulk Transporter after CARB’s public hearing in October.

Issues raised during the meeting included the “disconnect” between the current exemption for infrastructure delays, and how long the projects actually take, the definition of “commercially available” for different vehicle configurations, and how to account for trucks based in other states that make occasional trips to California.

And these aren’t considerations only for stakeholders on the West Coast.

Nevada Gov. Steve Sisolak in March made the state the 17th to sign a medium- and heavy-duty memorandum of understanding to accelerate electrification, with a goal of electric or hydrogen fuel cell vehicles accounting for 30% of MD and HD sales by 2030. Five states already adopted California’s ACT regulation, and Garland expects ACF to spread, too. That’s why leading fleets are taking the first steps to zero emissions now, whether they like it or not.

See also: Quantix spots another growth opportunity

Basso, vice president of maintenance at Quantix, detailed their nearly two-year journey to deploying two Peterbilt Model 579EVs—with the charging infrastructure to support them—in drayage operations during National Tank Truck Carriers’ 2022 Tank Truck Week, while Garland, a grant writer for Peterbilt, provided insight on funding available to help.

“You could buy an electric truck today—but it’s going to take at least a year to install your infrastructure,” Basso said. “We learned that the hard way.”

Advanced Clean Fleets

The proposed ACF regulation would apply to MD, HD, and off-road yard trucks in drayage and government fleets, as well as private, or “high-priority,” fleets with $50 million or more in gross annual revenue that “own, operate, or control” 50 or more vehicles with a gross vehicle weight greater than 8,500 lbs. Supporters asked for CARB to lower the threshold to 10 vehicles during the hearing, pointing to trucks’ impact on air quality in neighborhoods located near seaports, railyards, warehouses, and distribution centers.

Cocca didn’t expect CARB to lower the threshold, citing the ACF’s “common ownership and control requirements,” which establish individual operators, or contractors, as part of the larger fleet under whose authority they’re operating. But the concerns surrounding greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in “disproportionately impacted communities” spurred CARB to ban adding new diesel trucks to port registries after 2023.

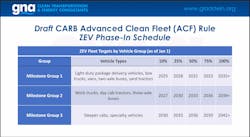

ACF calls for public fleets to make 50% of their vehicle additions ZEVs by 2024, and 100% by 2027; and for private fleets to either stop adding ICE trucks after 2023, or meet a percentage-of-ownership requirement that phases in ZEVs. These fleets would need to ensure 10% of their box and yard trucks are ZEVs by 2025, 10% of their daycabs and work trucks are ZEVs by 2027, and 10% of their sleepers are ZEVs by 2030. Each category scales up over time, ending with 100% of all fleet vehicles emitting zero emissions by 2042.

“Most of the large and medium-sized fleets we interact with are in favor of this rule,” Cocca said. “They see the benefits, and a lot of larger fleets already have sustainability goals that are part of their corporate ecology plan. The problems we see are in the differences between CARB’s projections and estimations, and the reality fleets have gone through in this process of electrification, or using hydrogen.

“So a lot of the concerns in the hearing surrounded timelines not making sense, especially with this passing in 2023.

“If you’re taking the purchase pathway for private fleets, your first purchase requirement is in 2024, so there isn’t a lot of time between when it passes and when it applies.”

The greatest concern voiced in the hearing involved infrastructure—and based on Quantix’s experience, those concerns are well-founded.

Quantix goes electric

The Houston-based chemical supply chain services company decided in late 2019 to pursue electrification as part of its sustainability efforts. “We haul the worst stuff on the road, so we felt like it was our job to lead this from the front and help figure things out,” Basso said.

Quantix considered hydrogen and renewable compressed natural gas (R-CNG) before settling on electricity. Basso said they learned hydrogen fueling stations aren’t feasible to own because they cost “millions of dollars” to build, and established infrastructure is geographically limited; and using R-CNG in their existing diesel trucks would have required an engine OEM change that made him uneasy. “What we found was, with electric, we could build our own infrastructure and control every aspect of the truck,” he said.

Basso predicted many tank truckers will “push the pause button” on EVs, and instead wait for the advancement of hydrogen fuel cells, which he believes will power most Class 8 trucks “at some point.” But Quantix wanted to learn how to use and maintain the vehicles of tomorrow, today. “We chose electric because pretty much every future technology we’re going to see in the industry will have an electric base,” he said. “Even the base power source for hydrogen fuel cells is electric. Once you get rid of internal combustion, you have to have it.”

After opting for electric trucks, Quantix had to identify the right application. Over-the-road wasn’t an option. You need chargers on both ends for longer runs, and while “opportunity charging” won’t harm the battery, Garland said, it’s currently unrealistic. Quantix’s 579EVs require 480-volt chargers to charge quickly, and Tesla stations are only 220. “That three-hour charge time turns into six if you’re not adding a Class 8 [fast] charger,” Basso said.

The carrier ended up placing the vehicles in its drayage operations in Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina, for several reasons. Both states have higher gross vehicle weight limits, so the extra 6,000-7,000 lbs. in battery weight isn’t a huge constraint in those locations. Also, they’re only dropping and hooking chassis, and not blowing or pumping out product, which could impact battery life. And, most importantly, the two port terminals feature newer buildings—with modern electrical systems inside.

Infrastructure planning

“If you’ve got a terminal on ‘the other side of the tracks,’ so to speak, and most of us do, and that terminal was built in the 1960s, 70s, or 80s, it’s going to cost you an arm and a leg, and possibly your firstborn to put the infrastructure in,” Basso explained. “Because at that point you’re replacing all the wiring in the building and adding circuit breakers. It’s a nightmare.”

Those relatively simple projects still took a year to complete—and that was fast, Cocca asserted.

The California Public Utilities Commission’s Yuliya Schmidt claimed during the meeting “energization” projects take 90 to 160 days on average, and the exemption for postponing ZEV delivery due to construction delays is only a year. “In many of our clients’ experience, that’s woefully insufficient to cover the entire process,” Cocca argued. “We’ve seen projects take from one to three years, or longer, depending on the fleet’s needs.” Schmidt also said 1 to 2 megawatts of power is enough to supply an “enormous” charging depot. “One megawatt is a small depot,” Cocca maintained. “What we see on average is 3 to 5 megawatts, which can take anywhere from 12 to 24 months to put in.”

See also: Report pinpoints top challenges for widespread battery-electric vehicle adoption

Large fleets must build out infrastructure for all their vehicles, not only the first 10%, which requires more real estate and takes longer; and the exemption is based on beginning construction, which is only half the process. “You’re 50% of the way through your project if you’ve already started construction,” Cocca said. “A lot of time goes into land acquisition, permitting, and other planning before the first shovel hits the ground.”

That’s why it’s imperative to start early—even before the trucks are ordered, Basso said.

The infrastructure and chargers for the two locations cost about $180,000, which was less than expected, he added, because both were well-suited for fleet charging. To control costs going forward, the carrier is charging its trucks only at off-peak hours, which can save $100 a “fill-up,” according to Charleston Electric.

Partnering with Peterbilt

Peterbilt helped Quantix save money on infrastructure, assigning an experienced fleet electrification liaison to work with local power providers to identify site capabilities and limitations, and what was most cost effective. The vehicles finally arrived in August, nearly two years after Quantix first approached Peterbilt in November 2020. The wait included the infrastructure projects, truck build time, and long grant funding process. “I’d love to tell you that’s an exception and it’s usually only five months,” Garland said.

“It’s not. This is a good case study.”

In addition to thoughtful route planning and infrastructure installation, tailored electric vehicle operation and emergency response training is key for drivers, and towing and wrecker services, Basso said. A good rule of thumb with Peterbilts is not to touch parts connected to orange wires. “Everything on the truck can kill you,” he said. “It’s 480 volts. It’s going to hurt a lot worse than when you stuck your finger in a light socket as a kid.” Garland said any short will shut off all high-voltage power, but questions remain about how fuel haulers will certify EVs as intrinsically safe for loading racks, Garland and Basso acknowledged.

Deploying the trucks also adds up-front costs, complexity, and capacity constraints, but customers increasingly want carriers to haul their freight with ZEVs, so Basso said they should help, too, possibly by installing their own charging systems for unloading or return trips. “If we’re going down this road, our customers have got to own part of it,” he insisted.

Helping hands

Owning two hand-built 579EVs didn’t come cheap. According to one local report, the trucks cost $350,000 each.

Fortunately, Garland also helped Quantix find and apply for financial assistance.

In this case, with no state funding available, he secured $1.3 million through the U.S. EPA’s Diesel Emissions Reduction Act (DERA) program by partnering with the South Carolina Ports Authority and other customers to test eight electric trucks.Peterbilt’s 579EV is one of several tractors eligible for up to $180,000 in incentives through CARB’s Hybrid and Zero-Emission Truck and Bus Voucher Incentive Project (HVIP), which recently was approved for $1.7 billion in additional funding. DERA is one of many diesel replacement, or “scrap,” programs. Other opportunities include point-of-sale and rebate programs, and tax credits for EVs and chargers.

“[But] you better order the trucks before that grant gets approved because they’re a year out,” Basso said. “So you’ve got to work with an OEM partner who will let you order the trucks, but wait until the grant is approved to pay for them.”

Organizations like GNA assist companies on their journeys to electrification, too.

Cocca expects public charging to play a key role, along with innovative “as-a-service” companies, like Voltera, which provides charging infrastructure as a service, and Zeem Solutions, which offers “EV fleets as a service.”

“Decarbonization is incredibly important, but there are headwinds to overcome related to the length of time it takes to acquire vehicles, and design and construct EV charging facilities, as well as the upfront costs, which are significant,” Cocca concluded. “Fleets are seeking an economically viable path to sustainability, but there are a lot of concerns about the economics of an ‘all-in-on-ZEVs’ transition.

“We hope CARB looks for ways to take fleet economics into greater consideration.”

About the Author

Jason McDaniel

Jason McDaniel, based in the Houston TX area, has more than 20 years of experience as an award-winning journalist. He spent 15 writing and editing for daily newspapers, including the Houston Chronicle, and began covering the commercial vehicle industry in 2018. He was named editor of Bulk Transporter and Refrigerated Transporter magazines in July 2020.